Aesthetics

Created: Tue Sep 30 2025

To better understand environmental aesthetics, I think I also need to understand more generally what do philosophers mean by the word "aesthetics". The word has been co-opted by social media, although haven't heard it as much lately but people calling things "aesthetic" for everything, or trying to make things "aesthetic". In contemporary usage and in social media, it's about framing and presenting a moment in the best possible way to showcase a visually pleasing scene and in turn, engagement and can elicit desire and jealousy rather than appreciation. Anyway, getting side tracked with this thought.

Notes on The Concept of the Aesthetic from Stanford Article

18th century is when philosophers started to talk about the term 'Aesthetic'

Topics within this domain that's covered is:

- Taste

- Objects

- Judgement

- Attitude

- Experience

- Value

Taste

18th century, because of rationalism -> beauty. Think disinterestedness, being able to have an opinion indepedent from your personal belief. On the surface, this sounds great because this means we can have the same language to talk to one another about the same thing that we are experiencing. And in this case, what we consider beautiful. But, then, the question becomes, who gets to dictate what is beautiful and who decides on the language? And is there no value in the subjective?

Egoism -> Virtue - Before reading more, this is an interesting point in relation to taste. It sounds like to have good taste, maks you a good person.

Immediacy

"the immediacy thesis—is that judgments of beauty are not (or at least not canonically) mediated by inferences from principles or applications of concepts, but rather have all the immediacy of straightforwardly sensory judgments. "

- What I've been thinking about for our relationship to nature and how to apreciate it. It's our senses, and usually sight/visual, is what we take in first. But where I am now, is that over time, how do we maintain this aesthetic experience or feeling over time.

- It's not reasoning, it's sensing that provides our aesthetic experience. British philosophers going against the rational view.

"Some species of beauty, especially the natural kinds, on their first appearance command our affection and approbation; and where they fail of this effect, it is impossible for any reasoning to redress their influence, or adapt them better to our taste and sentiment. But in many orders of beauty, particularly those of the fine arts, it is requisite to employ much reasoning, in order to feel the proper sentiment." (Hume, 1751, Section I)

- Interesting use of the term "species". To Hume, there are different variations of beauty and by thinking about other forms of beauty, it can help us understand how to look at beauty in art. Also reminds me of philosophy of art and how some philosophers think that in order to define what is art, we have to look at each discipline. Genus theory.

- Here, Hume is comparing our aesthetic experience with animals and art. With nature, we do not have to reason our taste, or our ability to recognize beauty in animals, but with fine art, we do. One is taking it for what it is, while the other is a cognitive experience.

- Of course, the critique here is that art and nature are not the same. Nature is not made by humans, while art is.

- Hume, Schftesbury, Hutcheson and Reid, philosophers regard taste as "internal sense"

- Internal sense, different from our five senses, is something that happens within the mind. We perceive the object's beauty through its nature and structure. It's not the formal qualities that we can directly sense through sight, touch etc, but it's something that is from the object itself. So perhaps when we consider something ugly, it's not true to its nature and structure. For example, using metal and hard materials to create a cozy living room. A cozy living room's nature/structure should feel welcoming and warm. There's a misalignment which causes this ugly aesthetic experience. So we also need to know the context and the nature of the object in order to provide an aesthetic judgement. Although, I'm not sure if this is what Reid was saying exactly, because this also sounds like you need to reason, or maybe I'm providing a reason to this theory.

Disinterest

- Egoism about virtue - judging an action, you take pleasure from it and serves your interets.

- Hobbesian - "to judge an action or trait virtuous is to take pleasure in it because you believe it to promote your safety". There's a lot to unpack here and the article doesn't get into detail because it's an overview, but what I'm thinking is that this safety Hobs is referring to is about power. It's about maintaining where you are or moving up the social/economical class. (Can expand into contemporary view, about fashion and advertising and what people consider beautiful and how it maintains their safety).

- "But pleasure in the beautiful is not self-interested: we judge objects to be beautiful whether or not we believe them to serve our interests." This refers to the idea that we can consider something beautiful without it benefitting us. Finding pleasure does not mean it has to serve our self-interest.

- Kant and disinterest thesis - "pleasure in the beautiful is disinterested". That this aesthetic experience does serve our self-interest.

- "To judge an action to be morally good is to become aware that one has a duty to perform the action, and to become so aware is to gain a desire to perform it." If something is ethical to you, and it aligns with your values, then you will take action on it. For ex. Beauty leading to environmental protectionism. Although for Kant, he thinks we do not take action on what we find beautiful, but I think he's wrong. He thinks beauty is disinterseted and contemplative.

- "Why have we come to prefer the term ‘aesthetic’ to the term ‘taste’?" One is adjective, the other a noun.

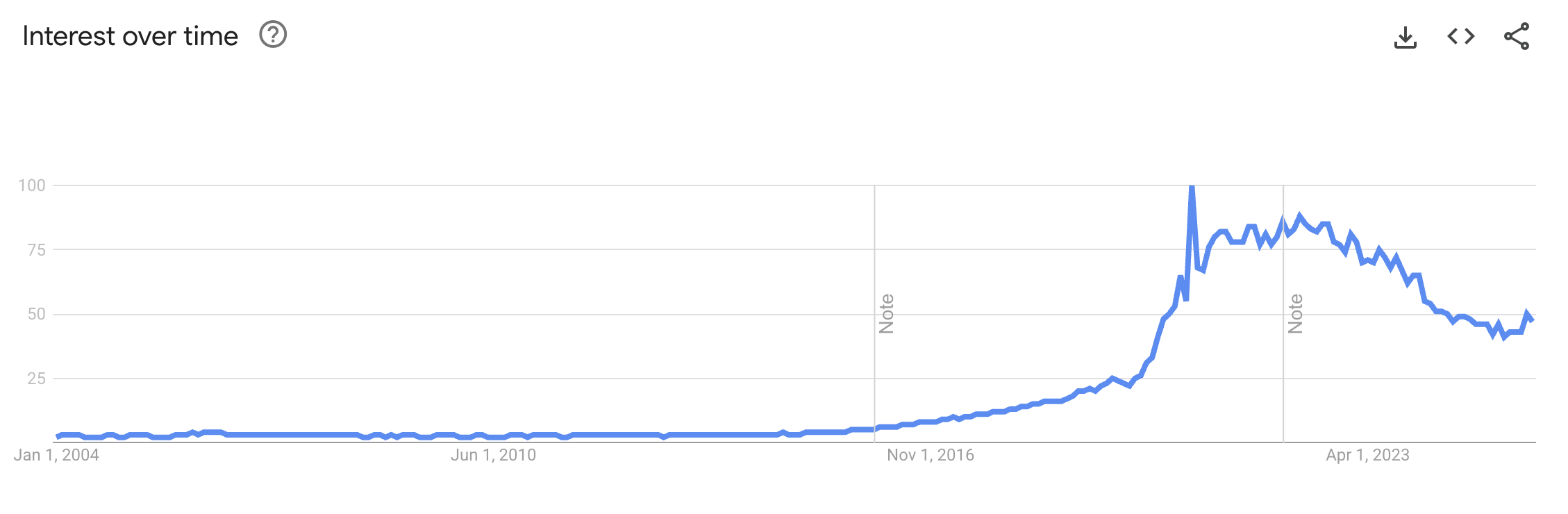

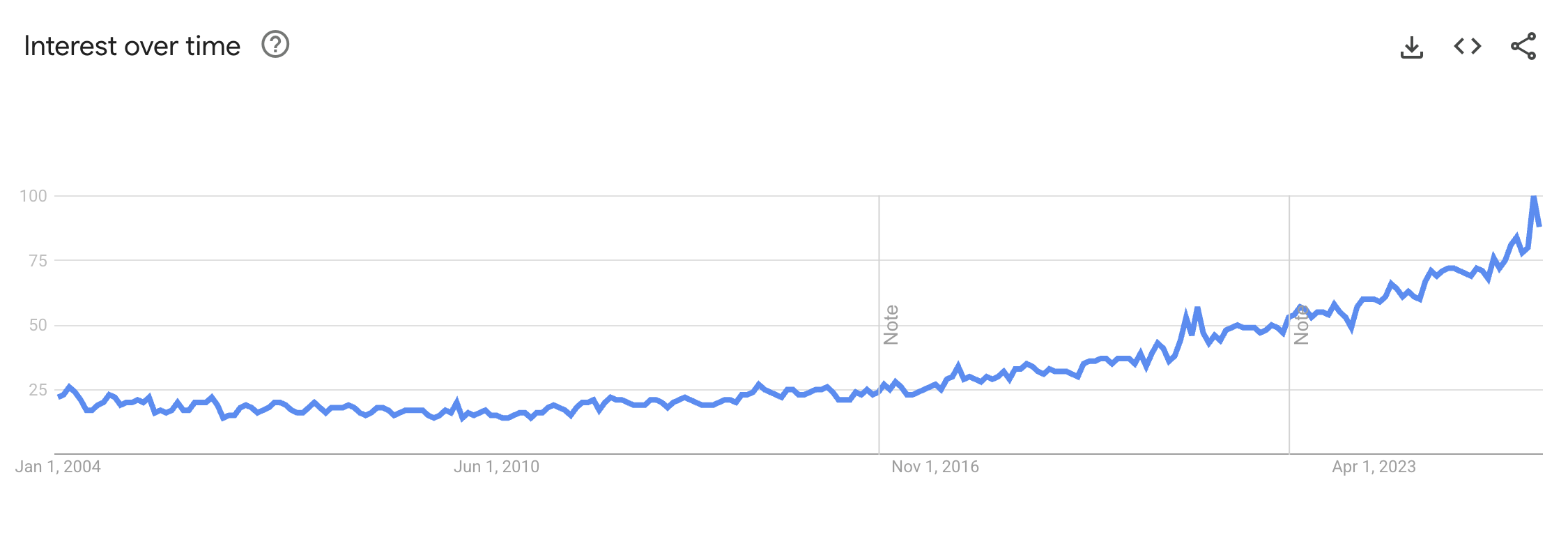

Looking at Google Trends, to suppor this claim of favouritism, there's a clear interest of the word over time.

Aesthetic - Google Trend 2004-Present

Aesthetics - Google Trend 2004-Present

Many reasons why this is the case but as mentioned previously, I think social media plays a big part, and our obsession with the beautiful because of social media. Back to the article.

- Aesthetic -> Greek term for 'sensory perception'. This aligns with an aesthetic experience having to deal with our senses, and the immediacy of the experience.

- To have an aesthetic requires all of our senses, not just our external, but also our internal. -> "As our language … contains no other useable adjective, to express coincidence of form, feeling, and intellect, that something, which, confirming the inner and the outward senses, becomes a new sense in itself … there is reason to hope, that the term aesthetic, will be brought into common use. (Coleridge 1821, 254)". Something here about inside/outside. About a new sense, the aesthetic sense.

Aesthetic Objects

- Formalism

- Conceptual art, an opposition to formalism. ex. Warhol's Brillo Boxes

- Arthur Danto "(a) another object that is perceptually indiscernible from it but which is not an artwork", meaning that there's something similar to this object, but it's not an artwork (banana on wall with tape). "(b) another artwork that is perceptually indiscernible from it but which differs in artistic value" (banana on wall with tape but in an art context, positioned in the artworld)

- perceptually indiscernible in this case refers to, two objects that are exactly the same through formal qualities, we do not know the difference between the two. The only difference is the information we are given about them and their context. This is similar to Hepburn's idea of "realization" (or is it realization?), he has a part about a series of words which could be gibberish or be poetry. And when you are told that it's poetry, then we will evaluate it differently. This is the same idea with Danto's claims.

- But, what if Brillo Boxes were never art to begin with? Meaning, what if Andy Warhol, the artworld, and critics got it wrong? Then this would be discounting conceptual art, and the ideas behind them and the cultural production around them.

- If people from the 18th century saw art of today, would they be able to judge it? For example, the Brillo Boxes as Danto points out that they wouldn't because the art of today is done within a historical and cultural context. The art leading up to today has influenced what is art. Which also means, will the definitions of art or aesthetics change? Yes, and as it should. Because nothing is static. Language evolves, words change meanings over time, and why wouldn't art or aesthetics change? And as new mediums arise, this will allow for new forms of expressions (ok, new forms, so going back to formalism then...). But if philosophers only had paintings as a way to judge aesthetics, then how would they be able to judge lets say, an interactive piece? This is a completely different experience and two different mediums.

- "If an object is conceptual in nature, grasping its nature will require intellectual work. If grasping an object’s conceptual nature requires situating it art-historically, then the intellectual work required to grasp its nature will include situating it art-historically." Here the idea is that we have to think about the object and not just look at its formal qualities to understand it. But what line of thought? What the author is saying is that history matters.

- "grasping the nature of an object preparatory to aesthetically judging it is one thing; aesthetically judging the object once grasped is another." The first part sounds like maybe it's about our initial thoughts on what we are seeing, whether it's formalism or what we think the artist is trying to say. Then there's the latter, where once we have more information, whether an artist statement or description of the work, or insight into their process, or knowing about art history, then we can judge it differently. Perhaps this is a comparison between the amateur and the critic.

Notes on The Problem with Calling Something “Aesthetic” by Gabriel E. Lipkowitz

"aesthetics is not only a way of seeing the world, but a way of thinking about it." Not just about our senses but the cognitive aspect. What do we think about the world because of our senses. And maybe not so much think, but the way we perceive the world.

"A truly “aesthetic experience,” as Iliescu writes, requires us to “slow down our sense of time.”" Relates to our fast paced life. Connects to the "we have ourselves become foreign to our everday" by Hepburn. The question is, how can we slow down our sense of time. I've experienced this with field recording. Standing still for five minutes seems like eternity to me. But recording has forced me to be still.

" Iliescu explains that “each aesthetic experience is unique and tied to a specific place, time, and individual.” If everything is subjective and unique, then how can we come to terms with a collective experience? There has to be something that unites the experience that everyone can agree on.

Notes on Santayana at the Harvard Camera Club by Daniel Pinkas

A paper discussing the lecture given by George Santayana (which I'll use Sat. for short) titled "The Photograph and the Mental Image".

- Ontology of photography. The being of photography, what are its properties? What makes photography?

- "realist" film theory (TBD)

- pg. 6: Sat. argues that photography is not an "ideal art". For Sat. ideal art is making with human interest, where photography to him is a mechanical reproduction of reality, it's a replical of reality. Here I would assert that perhaps photography can be a mechnical reproduction if the aim is to document what we see rather than using photography to capture an essence or property of the object that we cannot get through with our eyes.

- Ok, so Sat. says photography can be fine art if it's “governed by a desire for beauty and [...] productive of beautiful things”(Phmi 399). Which speaks to my previous point, but I guess there's a distinction for Sat. of what's the diff b/w fine art and ideal art.

- But even when photography came out, it didn't really depict reality as reality because of the limitation of the medium, resolution, colour etc. So, I still don't get why it was a concern. I guess it's in hindsight from my point of view, where photography has evolved and improved so much that it does seem more like a mechanical reproduction to me, but in the 1800s? I don't get it.

- The purpose of the paper is to view the lecture within the context of media and art history and photography's ontology.

- Two concepts: pictorial transparency and medium-specificty. The transparency thesis, if it's so obviously wrong why do we still consider it? Why are still discussing it...If we have to always talk about it in the context of photography's being, then does it mean it has some validity? Or is it more so to show, this is what photography is not, which is also useful.

- Club, artistic and scientific side. So, here are the two uses of photography, for creation and documentation.

- "no work and lots of fun" ""You press the button, and we do the rest"". Quotes from Alfred Stieglitz in a 1897 text in American Annual of Photography. Sounds oddly similar to AI of today. And from Pinkas, “photography without pain, without technique, and therefore open to all.” [Pinkas, 2024, p. 9]. Speaking to making photography into a business.

- Anamorphisis. Using mirrors to distort the image. Using the hardware as a way to explore image making. Note: how can this be

- p.11: Democratization of photography through enterprise (Kodak), gave birth to a new photographic aesthetic "straight photography".

- Why Pinkas directed me to his paper

- "In his understanding of “straight photography”, framing and shooting encapsulate the very essence of the photographic act, an act that culminates indeed in the “pressing of the button” but under the guidance of a conscious and sophisticated perceptive operation. The expressions “instant recognition of subject and form”, “spontaneity of judgment” and “composition by the eye”, are some of the ones used to designate what precedes and determines the decision to “press the button”. A concept that became more or less axiomatic among practitioners of “straight photography” is that of “previsualization”, referring to a way of visualising imaginatively the final result before pressing the button."

- I talk abot framing with photography and noted that it starts with us pressing the button. But even before pressing the button, we are making a mental image which also acts as a frame.

- “Percepts, or as Santayana calls them “mental images”, are useful for survival and reproduction because we are able to retain and reuse them.” [Pinkas, 2024, p. 12] Evolutionary perspective, to have images is a way for us to survive because we can use these images to help us guide the world around us. But how is it different than from someone giving me a warning, versus seeing the warning? HEaring about something allows me to be cautious while seeing the image, allows me to avoid the danger since I know what to look for.

- So there is talks about the difference between writing and photography.

- “The photograph carries out the function imperfectly fulfilled by the mental image. The virtue of photography is to preserve the visual semblance of interesting things so that the memory of them may be fixed or accurately restored” (Phmi 395-396). Writing served a similar function (it is “an artificial memory for words, and through words for events and ideas” (Phmi 396), except that writing (and speech, which he controversially classifies as an invention ) supports human memory by retaining things that have already been shaped by the processes of understanding, abstraction and verbalisation, while photography “rescue[s] from oblivion the most fleeting portion of our experience —the momentary vision, the irrevocable mental image” (pg. 13). Mostly quoted from Sat. Writing -> process of cognition and understanding, while Mental Image or photography -> about the moment.

- ““the mental images which we most dislike to lose [are] the images of familiar faces. Photography at first was asked to do nothing but to embalm our best smiles for the benefit of our friends and our best clothes for the amusement of posterity”” [Pinkas, 2024, p. 14] . Quoting Sat. It seems like photography was always about presenting our best. Reminds me of the seminar with Nova where I created a podcast about the best photo, but in the context of our mobile devices and how Google and Apple select the best photos for us if there are multiple of similar ones.

- Sat. "photograph for being so transparent a vehicle" "The photograph is “a literal repetition” of what it depicts (Phmi 399)." Pinkas makes the connection to the Transparency Thesis by Kendall Walton.

- p.15 "According to this view, when we look at photographs, we literally see the objects photographed." This aligns with the documentation / scientific in the sense that a photograph can depict reality. However, the difference is that for Sat. and Kendall, they meant that we actually see through the photograph and see the object. Pinkas goes on to explain that obviously this is absurd. If we are to actually see the object, then we would also be able to touch it. But no matter how a photo captures an object, it is not an exact replica due to hardware. Even with digital cameras and screens, they will have variation in colour and resolution.

- Pinkas offers two arguments against this and draws upon Noël Carroll and Berys Gaut. Carroll and his bodily orientation argument states that we cannot orient ourselves to an object through a photograph. In comparison to a binocular, which acts similarly to a camera in the sense that it frames an object and moment, but the binocular still allows us to know which direction the object is placed in relation to our body. This is because we are still in that environment or moment. Second argument built from Gaut, is the uninterrupted light transmission. This is more scientific in the sense that it's talking about how we are not seeing the light from the object in the photograph but instead light that is bouncing off of the photo itself. Here Pinkas clearly and definitively states photos are "opaque" like paintings.

- Sat. acknowledges photography can be functional and also artistic.

- pg. 18 Sat. says "These products of creative art are shadows rather than replicas of reality and present things as they could never have existed". Saying that photographs are still replicas of reality. But as Pinkas points out, photography are shadows since we see it as a photograph and not as reality as is. Clearest point is flattening a 3D space to 2D.

- p.34 The MSA thesis is something that I've carried with me as a designer. I always try to design according to the medium's properties. The quote “Why should we sacrifice all manner of aesthetic excellence in order to secure the purity of the medium?” from Carroll, it suggests that we don't always have to use the medium's properties for it to achieve a successful art. For example, photo realistic paintings. This is excellence and not using painting's properties. I would also add that there's subversion of a subject's expectations that adds to the aesthetic judgement. But this subversion, can it only happen when a new medium, it's successor's is in being?

Notes on Philosophy of art: a contemporary introduction by Noël Carrol

Reading Chapter 2: Art and Expression, pages 58-106

Part I - Art as Expression

- Art as expression, versus art as representation (mimesis).

- 19th c. artist moving towards subjectivity "'inner' world experience" (p.59). Romantic movement.

- Wordsworth - this author came up in other readings too.

- that poetry “is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings.”

- Objective world vs subjective inner world

- “Romanticism profoundly influenced the course of subsequent art. We still live in the shadows of Romanticism. Perhaps the most recurrent image of the artist in popular culture today remains the emotionally urgent author (composer, painter, etc.) trying to get in touch with his or her feelings.” [Carroll, 1999, p. 60] The portrayal of the artist and how emotions play a part in their work. The question I have is can an artist be emotion-less, attach-less, to their work. Can it be seen as a job where we can separate our identity from the work? This is more so a question for designers. I always think no, but I'll explore this another time.

- Romanticism was an attractive new way of doing art because it gave it purpose. Meaning, if art was mimesis, representing the real world, it could never compete with science. For art, it is about exploring and expressing emotion. (p. 60)

- p.61 - Etymology of expression, comes from Latin and means "pressing outward". In the context of art, the artist is able to bring out feelings from the audience/subject. Leo Tolstoy - expression as a form of communication. Well, sure, but how in art versus me expressing my frustration verbally.

- p. 62. Conditions of art: "an artist, an audience and a shared feeling state". Still not satisifactory, me sharing my annoyance about the traffic on my way to work and a co-worker feels the same, is not art.

- p. 63 “a distinction between the artistic expression of an emotion and the mere ventilation of an emotion”. Case and point from previous note. Ranting in the moment of frustration is not art. Deliberation act of trying to convey an emotion is. And it's usually a process. The process of making and seeing and reflecting, brings the artwork closer to what the artist had envisioned. Could this also extend to not just one artwork, but a series? To capture the depth of an emotion.

- p. 65 "publicly accessible medium" meaning that art uses a language that is recognizable by the public. This is how we can recognize and appreciate it. "lines, colors, shapes, sounds, actions and/or words"

- Formualaic expression theory of art: x is a work of art if and only if x is (1) an intended (2) transmission to an audience (3) of the self-same (typeidentical) (4) individualized (5) feeling state (emotion) (6) that the artist experienced (himself/herself) (7) and clarified (8) by means of lines, shapes, colors, sounds, actions and/or words. pg. 65.

- Tranmission theory and solo expression theory. TT is the one above which includes condition 2, while SET is without condition 2. SET is tempting because it means that there doesn't need to be an audience and it's what I think, most people would think what art is and how it differentiates from design.

- “He says that he does not want an audience, but by employing a natural language he makes something designed for public consumption.” p. 67. By using any type of language, words, sounds, visual, that another person is able to understand, then the artist is making art for an audience because it's a shared language. It's still intended for someone to view/experience.

- Carroll also goes on to argue that the artist is first and foremost their own audience. They make for themself as they are the ones revising the piece.

- TT is about the clarification of emotion yet not all art does this. p. 72, symbolist art, vague emotions. "Symbolism is an art of intimation in which feelings are prized for their elusiveness."

- Surrealist artists and "Exquisite Corpse" where one person writes a line of a poem, fold ths paper, and pases it on. Here there are multiple artists writing different, random things, with no intention of clarifying an emotion. If anything, it's a state of confusion and cognition since we will try to make sense of what we are reading, or try to make meaning, rather than feel something. "aleatoric art"

- “Some art is about communicating and/or exploring ideas.” p. 74. Performance art. Found objects. Op art. As Carroll says on pg 75, it's cognitive, meaning we have to think about what the art is trying to communicate rather than make us feel.

- “Conceptual Artists are generally opposed to what they regard as the commodification of art. To resist commodification, they specialize in artworks that can’t be sold—artworks that are ideas, rather than saleable objects.” p.77. If it's an idea, this idea still needs to take form somehow. How is this idea being communicate to one person to the next? It is not through telepathy. There has to be an exchange of words, whether text or spoken. Carroll says that an artist is able to mentally come up with art, and then document it, it is still the mental performance that was the artwork rather than the documentation. It's similar to if I were to document a painting I made through a photograph, the photograph is not the artwork, it's still the painting.

- With Conceptual Art, the last condition, the list of how the artwork can come to be through lines, shapes, colors, sounds, actions and/or words remains incomplete.

- Carroll ends Part I, that there are everyday examples that meets the conditions of expression theory of art. The example provided is an emotionally charged letter about an ex.

Part II - Theories of Expression

- Expression as representation: How it's used in language but not in philosophy of art since expression is talked in contrast to representation.

- Expression as communication: "It's raining cats and dogs"

- Philosophy of art, expression is about emotion.

- Reporting emotion versus expressing emotion. '“You numbskull!” with “I am angry with you.”' pg. 80

- “The concept of expression that interests philosophers of art ranges over human qualities such as emotive qualities and qualities of character. For our purposes, expression is the manifestation, exhibition, objectification, embodiment, projection, or showing forth of human qualities, or, as they are also called, “anthropomorphic properties” pg. 80-81. The idea of “anthropomorphism keeps on coming up, with personfication of rivers, scientific view of the world since it's our projection onto reality through our observations and senses. But is everything anthropomorphic then if it's our projection?

- “But how do we go about attributing expressive properties to artworks?” p. 81. A more interesting question I think because it requires perception but then cognition.

- "sincerity condition" states that the artist has an emotion, they have experienced it and they are trying to get it across in their art. Does it mean that this feeling has to stay constant while making the art? Or can it not be that they have once experienced this joy and they are trying to recreate it throught their art? Chasing the emotion.

- pg. 81 "The outward manifestation of nervousness is linked (some would say conceptually) to her inner state." Talking about a person talking and her voice quavers signaling to us that she is nervous.

- “We do not require genuine sincerity from actors; after all, they’re actors!” Acting as a form of art, do not require sincerity since they are acting. They are portraying an emotion rather than having that emotion internally. pg. 83

- pg. 83 - "much art is commissioned." When art is commissioned, this means the spontaneity of expression is removed and instead calculated and uses formal devices to get the emotion across.

- pg. 84. Arousal condition: "in order to express x the artwork must move audiences to feel or experience x". Example by Carroll, "A piece of music can express hope, and I can apprehend that it expresses hope without becoming hopeful myself, just as I can see that George has a happy face without becoming happy every time I see George." It's saying for something to be art, it also needs to move us, for the artwork needs to penetrate us and be able to incite the same feeling that it aims to express. But we can recognize an emotion without having to feel it. "If you say the weeping willow tree in the front yard is sad, I can see what you mean—I can detect the relevant expressive properties—without becoming sad myself."

- p. 87. Exemplification. When we see a sample of something, but we do not consume or take the sample, but the source, the sample is a symbol. The example Carroll gives is seeing a paint swatch but receiving the paint can, or seeing a dessert tray with an array of sweets to view the options before consuming the actual piece of slice of cake that awaits us in the kitchen. Exemplifcation as a form of symbolism.

- pg. 88 "Exemplification is a common form of symbolism, but it is not the same as representation. The domain of representation is persons, places, things, events and objects. The domain of exemplification is properties." "expressive artworks exemplify the properties that they express" Meaning, artworks is showing you an example of an emotion, but it is not showing you the whole emotion. We are only see parts/properties of the emotion.

- scherzo: a vigorous, light, or playful composition, typically comprising a movement in a symphony or sonata (oxford def).

- pg. 91 “According to the exemplification theorist, metaphors involve the transfer of one set of labels from an indigenous field of application to an alien field.” Example C. gives is King Richard the Lion-Hearted. King Richard does not actually have a lion heart, the quality of a lion heart does not exist in humans. In this case, we are not projecting our human self on to nature, we are projecting nature onto us.

- p. 92. “Metaphors, then, are always homologies.” Metaphors are appropriate when the label mapping is in accordance with what's it's being mapped to. Hot headed person vs cold shoulder. Temperature labels to human traits.

- "one-off metaphors" pg. 94. metaphors that do not "belong to a scheme of contrasts".

- Talking about metaphors bc this is how we attribute expressiveness to artworks...or it isn't since there's another section. But I'm also wondering, will there ever be a theory that works?

- "dead metaphors". when they become real, "hands of a clock" p. 101. What are metaphors in digital space that we've taken from analog that is now a dead metahpor?

- Dead metaphors become real in how we see or maybe how we understand what we see. Before, did people really associate hands of a clock with a hand? According to this English stackexchange, it's not really understood why it's called hands when they resemble more like finger, or an arm. Project idea: make a clock with hands as a way to not tell time. Or as the hand makes numbers. Finger counting.

Notes on Collecting What? Collecting as an Everday Aesthetic Act by Laura T. Di Summa

The paper looks at how collecting objects is part of our everday aesthetic choices and how it contributes to our identity. That by collecting objects, it aims to clarify and re-enforce our identity. Collections do not just have to be for art collectors but for someone not in the art world, collecting isn't always tied to economics.

p. 256 “Instead, collecting in the everyday, and if I may, collecting the everyday, is typically open to personal quirks, oddities, and unspoken preferences.” I wonder about hoarding. Of course this relates psychological and mental health but are there also underlying aesthetic choices being made?

p. 257 "Collecting, and especially the collection of art, can be traced back to the Hellenistic period;" We've been obsessed with collecting. It can be a way for us to make sense of the world through similar objects. Is it also part of evolution that we need to find patterns to navigate the world?

Thought - Who affords to collect? This requires space, and as our living spaces become smaller and smaller (at least in urban development, and for the everyday), what does this mean for collections? How do digital collections contribute to our identity when they are hidden away. This reminds me of again of reading about digital photography and how images can be forget or lost when stored on hard drives or on the cloud. "Digital forgetting" is the terminology and then there's "dark archive" for images stored away, out of sight on a digital space.

p. 258 "‘ghost’ collectors" Wealthy and invisible people amassing art. I think the author starts with some historical and contemporary context to contrast the everyday act of collecting. To show the disparity, but to also show that it's a human condition.

p. 261 "One feature of aesthetic judgements is that they are often experiential" Meaning that these static objects relates to our experience of the world and our relationship to them (Melchionne, ‘Aesthetic Choice’, 283–98). Examples: The books I purchase will live on a bookshelf or bookcase in my apartment, and with limited space, I have to be intentional with what I buy. So how do I make these decisions?

To read "Autonomy and Aesthetic Engagement" by Thi Nguyen. "we often cherish the making of aesthetic judgements, for they require us to put our own efforts into it"

p. 261 "What’s important is less that the object collected is valuable, rare, or particularly coveted (even though I am not excluding that these factors can play a part), but that the object has been ‘found’ by the collector. In the act of collecting, there is a sense of adventure and discovery." In addition, the objects by themself is not valuable, but as a collection they are. Masterpiece vs a series of work. Solo artist vs musical group. p. 263 "Everyday collections are often assemblages of mundane objects, yet their effect can be powerful." When we see a collection of mundane objects, we see the effort of the collector. We see what the collector sees. We are able to at a glance, perceive the properties of this object as a whole. Is it that we are amplying the aesthetic property of the object by having it be in a collection? The amplification is what draws us in.

But why do these everyday objects matter in a collection? It matters to one person, the collector, is that not enough? Sure, but then why does it matter to the collector? To answer this, Summa draws upon "Freudian uncanny".

- "Surmounted primitive beliefs are based on animistic and magical phenomena we attach to objects and events in our lives. A feeling of the uncanny is triggered by the experience of coincidences; at other times, it is linked to objects that are seen as the repository of peculiar powers. It is possible to imagine objects in collections, especially unusual ones, having such a function. Their meaning can reside outside of them in ways that border the paranormal, but that nonetheless remain attached to their materiality as objects in this world." p. 263

The allure of objects. Why do we gravitate towards certain things? This can also be the same for natural entities. There's perhaps a power that comes with these objects that is unexplainable. "Experience of coincidences", does this mean that the object or thing reminds us of something? Going back to "expression in art" and metaphors.

“these objects are loved.” p. 263. There has to be love I think in order for someone to dedicate their life to collecting. Like dedication to a romantic partner, it takes work and understanding.

p. 264 "As Katrien Schaubroeck notices, reasons for loving are neither normative nor comparative (there is no need to justify why we love one person and not another)."

"eitology" study of causation of origination.

The idea of love could be included in thesis because there is a relationship that I have with the rivers, this connection, that could be described as love. No justification for the love, other than I find it beautiful, relaxing, scenic view, enjoyable, etc. After talking to Douglas, he said he doesn't have a working concept of what beauty is. Which is refreshing to hear because he studied philosophy. And I responded, do we need a concept of beauty if we can all agree on what we find beautiful? Or in this case, what an individual finds beautiful in an everyday object?

"collecting should be seen as an aesthetic and performative act independently from the objects collected." p. 264. The paper is examining the action rather than the collection as an object in of itself. To collect (and to also arrange/sort/organize) is part of the aesthetic experience. "What matters is the connection between such an act and identity." The action matters more than the actual collection itself. Meaning, the process. How we negotiate with our aesthetic judgements, and how they change over time.

There's a lot of things I want to collect. Once I started to collect cardboard, but maybe this was becoming an obsession and turning into hoarding because my laundry room was overflowing with it. And I also had a fascination with plastic bread tabs for their colours and text. I have some stamps and would like to collect more but that's a whole world that I don't know if I can get into.

"imperfection rather than perfection" p. 264.

Author talks about Marie Kondo, and yes, I also was into this craze and bought the book when it came out. Did I actually put any of it into practice, nope. I still live a very messy life but thankful for my partner who is on the other hand, a very organized person.

p. 265 "While minimalism and tidiness are appreciated, we may appreciate them so much because they are a way of ‘putting away’ a more personal side of who we are in a cathartic fashion." Could it also be that we want control, and it doesn't have to be about aesthetics? But then we could argue why have control in a space, by tidying up, we are also preferring a cleaner/minimal space. If it is about control, how are there things in our life, that we can not control.

organizing - against ornamentation.

"when collections at least evoke some kind of imperfection or messiness—we need not see such imperfection as a defect or an obstacle." p. 266. We shouldn't focus on the imperfections of an everyday collection. If anything, the imperfections should contribute to the aesthetic judgement and experience. The imperfection relates to the everyday.

Notes on Myth of the Aesthetic Attitude by George Dickie

- "psychial distance" and "disinterested" ... not physical distance as I original read. The distance is mental, but there could also be a physical distance in that, you do not embody the art whole.

- "psychial distance", Edward Bullough, states that "puts some object...'out of gear' with the practical interest of the self". pg. 56. Sheila Dawson, beauty disrupts our everyday life and brings us into an aesthetic consciousness. Meaning, beauty is not part of the everyday experience? This would be interesting to see it in the lens of "everyday aesthetics".

- Stolnitz: "disinterested" means "no concern for any ulterior purpose" ;1 "sympathetic" means "accept the object on its own terms to appreciate it";1 and "contemplation" means "per? ception directed toward the object in its own right and the spectator is not concerened to analyze it or ask questions about it"

- Motives and intentions to experience an artwork, whether it be music or paintings etc, can differ, but there is only one way to attend. Meaning, we listen to music the same way but each person may have diffrent reasons for listening to a piece of music.

- Eliseo Vivas "He defines the aesthetic experience as "an experience of rapt attention which involves the intransitive apprehension of an object's immanent meanings and values in their full presentational immediacy". When we view art in the way it's meant to be viewed, then we have an aesthetic experience. This is similar to what Hepburn was saying about "realization".

- "On the other hand, such distractions may turn into dissertations and whole careers." p.60 Such an unnecessary comment in his paper but also hilarious because you can kind of get a sense that he saw thinkers trying to make up something that doesn't exist. The fact that AA isn't talked about much after his paper is maybe a telltale sign that it's true (an obvseration made from the Internet Philosophy article).

- "'Disinterestedness' is a term which is used to make clear that an action has certain kinds of motives."

- Poem, rugby and cathedral image. Problem is the relevance to the artwork, rather than the aesthetic experience.

- Criticism not compatible with appreciation according to J.S.. Dickie rebuts with

- "Seeking and finding reasons (criticism) does not compete for time with appreciation".

- To find reason, or criticism, is to be aware and attentive. Isn't this what the aesthetic attitude is proclaiming? The person is paying attention, they aren't actually inattentive.

- "Finding a reason is an achievement, like winning a race". Honestly not sure about the analogy about winning a race. I guess it's that it's fast to spot a mistake or to find a flaw. What is this proverb "It takes to run a race but not to win it."

- Aesthetic value and indepedent of morality. Moral vision according to David Pole is either true or false (or both). To have a false moral vision means the work of art is "internally incoherent". Meaning, there's something off about the object, and the object isn't coherent which is an aesthetic judgement. A defective part of the work.

Notes from The Aesthetic Attitude on Internet Encylopeida of Philosophy

- "These theories, usually called aesthetic attitude theories, argue that when we take the aesthetic attitude toward an object, we thereby make it an aesthetic object." Meaning, when we are in the frame of viewing an object with aesthetic qualities, such as viewing an object with form, colour, etc.

- Aesthetic attitude is a frame of mind.

- Potentially be able to have aesthetic attitude towarsd everything if it means having the frame of mind for it and changing our attention.

- "Since there are things that we can take the aesthetic attitude toward that are not art, the aesthetic attitude is not just an artistic attitude. It is much broader than that." What is this broader lens that the author is speaking of?

- AA can be applied to beautiful and ugly things.

- "disinterest" - viewing an object without any personal interest. Meaning, what can this object do for me. To have a painting based on its monetary value is to view it economically, to contemplate its aesthetic qualities like colour and composition, is to have an disinterest attitude.

- "Disinterestedness, then, does not indicate complete lack of interest (finding something uninteresting), but a lack of personal investment or goal-directed interest." Meaning, you can find an element in a painting interesting, but it doesn't have to be connected to you as a person, and for personal gain. For example, the combination of colours in a Jackson Pollock painting is intersting to a viewer but it doesn't mean they will gain anything from it.

- Appreciating for its own sake. Similiar to how I see Simone Beaudevoir, Ethics of Ambiguity and the hierarchy of people making decisions. There's an adventurer type of person, and they only make decisions based on the fact that they can say they did it. To go on an adventure, to say you went on an adventure. Similar to experiencing something that is aesthetic, you are viewing it because you want to have this aesthetic experience.

- Can we truly just do something for the sake of it? This reminded me of a talk that I just attended at KIKK 2025 where Robert Hodgin talks about how he explores techniques in Houdini for the sake of exploration. I do the same with Processing. But the goal of learning is there, meaning we want to gain technical skills. It could be the same about the example that the author says about Islamic art and the museum goer. Meaning, they want to view the art for just the aesthetic experience, but there's also an education aspect to it.

- Nature of art -> explained by aesthetic attitude. But seen as insufficient because we also have aesthetic experiences with nature.

- Lord Shaftesbury, Immanuel Kant -> disinterest

- Arthur Schopenhauer -> aesthetic contemplation

- Faculty of taste - David Hume, Shaftesbury, Francis, Hutcheson. Taste to determine an object's aesthetic value. We can improve our taste through exposure and education. Edmund Burke criticized this.

- Hume, he didn't use disinterest but instead lack of "prejudice".

- "This is the crucial point on which all three theorists agree: they all share the central idea of disinterested pleasure as independent from personal interest, and it is this notion that forms the starting point for aesthetic attitude theories." The three theorists: Hutcheson, Hume, and Shaftesbury.

- Shaftesbury -> beauty equated with goodness and truth. To aesthetic appreciate is to morally appreciate. Morality and truth are different from aesthetic qualities, but for Shatesbury, to arrive at these ideas, we have to view an object through an aesthetic attitude. Meaning, that we need to be in this aesthetic frame of mind. Hume and Hutcheson disagrees, but there's a disinterest view from Shaftesbury that they all agree on.

Kant

- "According to Kant, aesthetic judgments involve four important aspects. They must be disinterested, be universal, exhibit purposiveness without purpose, and be necessary."

- All judgements of taste are subjective according to Kant since they come from our feelings. 3 types of satisfaction: the agreeable, the beautiful, and the good.

- The agreeable, serves our desires. We don't find everything agreeable. For example, take food preferences. I love potatoes, and I love french fries. My desire for crispy on the outside, and soft on the inside fries will be an agreeable experience for me because this is part of who I am. I crave certain foods, and so do other people. Which means we will find different food agreeable based on our desires/cravings.

- The good. Being charitable means contributing good to society. It's a personal interest. This act can also bring more generousity to other people. The good creates pleasure in ourselves knowing that we did good. This is interested pleasure.

- The beautiful. According to Kant, is disinterested pleasure. An object's existence is irrelevant for Kant. Whether you want an object to exist or not, doesn't matter for judging its beauty. Because if you consider its existence, then you are interested in it. For example, the Ontario place and the spa in Toronto. Many people, myself included do not want this spa because it means the land is being privatized and there's less green space. I've taken an enviornmental and econimcal standpoint rather than an aesthetic attitude. To make an aesthetic judgement, I need to have an aesthetic attitude.

- universal, purposiveness without purpose, necessary.

Schopenhauer

- Experience the world through the Will. Meaning, there are desires and we are in constant pull with our desires which are based in personal interest. To escape this, it's to view the world through an aesthetic attitude (he doesn't use this term). To contemplate on aesthetics, is to be not intersted in objects personally, and in turn, can release us from our suffering.

- We remove any relational viewing of an object, whether it's subject/object or object and its existence. We also focus on perception rather than reasoning. Representation -> contemplation. Last, is to view an object as representation is to see its idea. Similar to Plato's form. Aesthetic attitude is to contemplate and see the representation as Idea.

20th century

- Edward Bullough. Psychologist, "psychical distance". A metaphor for spatial and temporal distance. But also not emotional close to an object or thinking of its practicality. "over-distanced" "under-distanced"

- Jerome Stolnitz. AA is to attend to something and view it non-instrumentally, "This is just to say that we do not look at it as a means (as an instrument) to some other end." AA for J.S. is disintersested and sympathetic. Sympathy means to view an object independent from the artist or its function. To view "artwork on its own terms." Any moral judgement included is not an aesthetic attitude.

- "Stolnitz is a proper aesthetic attitude theorist who argues that we can adopt the aesthetic attitude toward anything." Meaning, anything that person decides to make into an aesthetic object, they can.

- Attention. "The thought of a cathedral that accompanies the poem is thus aesthetically relevant. However, it might also remind one of a personal experience, say, of one’s wedding that took place in a cathedral. This diverts attention away from the poem and is thus, argues Stolnitz, aesthetically irrelevant." So to think generally of a cathedral is relevant but then to think about it personally is irrelevant. How are we to think generally if we never had contact with a catehdral before? How does the personal association take away from the poem's meaning? If we are to think about a cathedral because the poem alludes to it, and we thought it through a personal connection, isn't this sufficient considering there's no direct verbage saying which cathedral?

- Facts can also be aesthetic relevant or irrelevant. "(1) do not weaken our aesthetic attention, (2) pertain to the meaning or expressiveness of the object, and (3) enhance the quality of one’s aesthetic response."

Roger Scruton and Aesthetic Attitude

- Pleasure, enjoyment, satisfaction. "If we thought there were no enjoyment of any kind we could get out of an object, we would not attend to it aesthetically." vs "aesthetic hedonism" which is the aesthetic value of an object is only its ability to give us pleasure. This can be seen with scenic tourism (in that, we are only taking in nature's beauty because it gives us pleasure). There can be pleasure (aesthetic satisfaction) in negative emotions too.

- Art for art sake. experiencing something for just its aesthetics. This claim I'm unsure if this is ever possible.

- Normative. "when we think that something is beautiful, we think that other people should find it beautiful, too." It's creating a norm through agreement.

- Scruton doesn't explicitly follow that AA is a state of mind and that we can switch to it at will. But instead "Scruton’s definition may actually come closer to the normal meaning of ‘attitude’, in the way that we talk about an attitude of disapproval or an attitude of hope. Here, we find attitudes of beauty, elegance, loveliness, their opposites, and so on." We have multiple aesthetic attitudes. This is brought up because to switch our frame of mind we have to be conscious that we switched to an aesthetic attitude, but we can often just say "that's ugly" or "that's beautiful" which are aesthetic judgements, and we do it sometimes automatically.

Crticism

- George Dickie. Argues against Scruton and Stolnitz since their claim is saying we have a special kind of attention or action when taking an aesthetic attitude. But for Dickie, he sees it as either we are paying attention or we are not.

- Watching Othello and the husband is thinking of his wife. The husband is not paying attention to the play. Although I wonder if anyone has talked about whether we can simulateneously be interested and disinterested? If we are able to multiple task, like walk and talk, could we not split our attention? Or is attention solely defined as being focused on one thing?

- Motives and attending are different. Music student is motivated to learn chord progressions for an exam. He is still paying attention to the artwork because he's listening to the chords.

- "To sharpen this, the idea is that there is no special mode of perception that corresponds uniquely to the way we perceive when we adopt the aesthetic attitude. There is only one way to perceive or attend to something, and that is just by looking at it or noting features of it."

Moving Forward

- "the aesthetic attitude is a point of view one takes. It is, in a sense, a way of priming our experience in which we mentally set ourselves up to pay attention to certain things."

Notes on The Aesthetic Attitude by Jerome Stolnitz

- An object that is "aesthetic" to Stolnitz is when we simply look at an object to just enjoy it.

- "harmony" -> "works of art which are found attractive or admirable by people of a certain historical period or a specific culture". Harmonious could be seen as agreeable?

- Aesthetic to Stolnitz: to perceive an object for the sake of perceiving it and to view it independently from its moral, social, political attachments.

- "Art has been explained and valued in nonaesthetic terms. It has been esteemed for its social utility, or because it inculcates religious beliefs, or because it makes men more moral, or because it is a source of knowledge." All of these examples are not intrinsic to the art itself. Meaning, what value does the art have as an object that we see and perceive.

- Artist no longer equated as craftsmen. pg. 31. This means that to make art is not about utility or function. Although craftsmen, also sounds like there's a master of one's crafts, which maybe can be true for some artists. Anyway, during the 19th c., artists started to be disgusted about our industrial society, "mass society". Artist trying to express their individuality. A push and pull between artist and society. Making art for art's sake and making an object for it's aesthetic perception only.

How we perceive the world

- Aesthetic perception -> Aesthetic attitude

- Making a connection between attitude and how we view the world? If I have a negative attitude (or outlook), then I will perhaps see the bad in everyone and everything. And attitude can also influence behaviour and how we not only perceive the world, but navigate it.

- "An attitude is a way of directing and controlling our perception." pg. 32

- "attention is selective" - goes against the notion that we were passively taking in the world. What about cases where we are mindlessly not paying attention? I guess that's being inattentitive.

- The attitude, helps us be prepared to respond and act accordingly.

- "an attitude organizes and directs our awareness of the world." pg. 33.

- "attitude of 'practical' perception" p.33 - Stolnitz suggests that we view the world through the lens of what can I do with this object and what can it do for me? So the service of an object. How can I achieve my goal with this object?

- objects as "signs" - traffic lights tell us when to go, slow down or stop. the practical aspect of the colours.

- p. 34. "perception has become economized by habit". But can this also not be evolutionary? That we need to find what it is useful for our survival and also development? I guess, how do we separate it now from our capitalist mindset.

- practical perception vs aesthetic attitude of perception.

Definition

- "disinterested and sympathetic attention to and contemplation of any object of awareness whatever, for its own sake alone" p. 34

- "disinterested" - "we do not look at the object out of concern for any ulterior purpose which it may serve." p. 34. Meaning that we are not seeing how this object can be of use to us, or how it can serve us in someway.

- "Another nonaesthetic interest is the 'cognitive.' i.e., the interest in gaining knowledge about an object." pg. 34. How would this hold up against Allen Carlson's view about Environmental Aesthetics? If we are seeing nature through a natural history and natural science lens, are we not viewing nature with an aesthetic attitude?

- AA -> "whole nature" that is, what is its being. What makes a painting? The brush strokes, the colours, the composition, etc. To buy a painting and to place it on the wall to show status is not to appreciate it for the painting but for its economic and social status.

- "disinterested" is not the same as being "un-interested". TO be un-interested is not to care or pay attention. To be "disinterested" we need to still pay attention, we are paying attention to form, colour, etc.

- "sympathetic" is to "accept the object on its own terms". pg. 36. To be receptive of what the object can offer us perceptually. Nature does this very easily, we are able to separate its utility or function sometimes maybe because we aren't bogged down with an "artist" or a human making it. When we view water flowing, we are able to view it for what it is, the colour, the reflection of the sun, the form of ripples, creates a mesmerizing and calming effect. This is the perception.

- "We must follow the lead of the object and respond in concert with it" pg. 36. But if objects are made from humans, and humans are making the aesthetic choices, should this not be taken into consideration of an aesthetic judgement? To only look at an object for its visual or perceptual qualities, would not be meeting at the object on its own terms.

- I suppose maybe there's a distinction between an aesthetic attitude, and aesthetic judgement? Because the aesthetic attitude is to take in the object as is, but perhaps an aesthetic judgement is then to take into consideration all the other points that make up the object, the artist, the context etc.

- The example of Americans not performing German composers during World War I is not being guided by an aesthetic attitude but instead their morals and values. It's the question, can we separate the artist from the art?

- pg. 37 "aesthetic perception is frequently thought to be a 'blank, cow-like stare'." Never really studied a cow's facial expression before but I suppose they have "no thought" in their expression. This idea makes it seem like to appreciate something aesthetically with this attitude is to "just look" with nothing deeper. But when we are experiencing a work of art, there are emotions that can take over us. We can feel moved. But can art not be a cognitive experience like that of with conceptual art? Then I suppose this wouldn't be an aesthetic experience.

- Aesthetic attention -> activity. Maybe moving eyes around a painting to examine it, walking around a scultupre to fully appreciate it, moving ones body when listening to music.

- pg. 38. Be attentive to the complexity and details of the object. This would also perhaps address the surface level reading of an object. But then J.S. goes on to say that people fail to "see" because they might lack the formal art training or an able teacher to point out the details, and mentions "it of requires knowledge". So, would this mean that aesthetic attitude/attention means that we need to learn about the art to fully appreciate? Would this also not suggest that there's a cognitive aspect to aesthetics?

- "work comes alive to us" -> when we have an aesthetic attention, the work feels alive. Think of a movie and how we can be transported out of the cinema or our couch to where the characters are, or how we can feel emotions overcome us as if the actors are right in front of us.

- Aesthetic attention - "alert and vigorous" p. 38. "contemplation"

- p. 39. No object is inherently unaesthetic.

- p. 39 "Indeed, the word 'aesthetic' is often used in everyday speech to distinguish those objects which are delightful to look upon or listen to, from those which are not." This is similar to "that's so aesthetic". Aesthetically pleasing.

- Wordsworth showing up again...p. 40.

- Awareness in adults, "intellectual", "nonsensuous knowing of "concepts" and "meanings," and their interrelations" - constnantly making connections based on our experience. this is different from the aesthetic awarness, for J.S. aesthetic awareness comes first, then the intellectual. Is this also aligned with human development?

- "awareness" -> "product of imagination or conceptual thought, can become the object of aesthetic attention" pg. 42.

- "The value of the aesthetic experience is felt in the very experience itself" pg. 42 "intrinsically valuable". The value doesn't exist outside of the object or experience. Meaning, the facts, the artist, or consequences. -> "disinterested contemplation"

- St. Thomas Aquinas, medieval thinker. "that which gives pleasure when it is merely looked upon"

- 18th c. Kant, aesthetic disinterestedness. "satisfaction". doesnt' go in depth with Kant, or anything at all really.

- Is human existence then about just being practical and having an ulterior motive? This is what an aesthetic attitude is trying to go against.

- Does an aesthetic object need to be instrumental? Meaning, to be practical to have of use to the viewer?

- p. 44 "The absence of aesthetic value from life is often the result of being-efficient-and-no-non-sense-about-it." So does this also mean that there needs to be time and care from the creator too? Meaning, if a person needs to approach with an aesthetic attitude by slowing down, should this not be applied to the creation of the object as well?

- When we are thinking about how we can use the object, for future gains, we have "an eye to the future". This diminishes the aesthetic experience.

- aesthetic attitude vs practical perception. not separate from one another.

- addressing the fact that we can essentially multi-task.

- "attentionis always a matter of degree" pg. 45

- Form and function working together.

- Now the question of art vs nature. Which one is more valuable aesthetically? One argument, art can be reproduced and shared, while nature is highly localized and transient. pg. 47. But can we also not take a photo of nature and have this be shared? Also, what happens if we have only "ugly" nature. How would this affect us?

- J.S. also mentions the frame vs unframe statement. Now I wonder where is the first instance of this. This book was written 1960, where Hepburn's paper is 1966.

- "We might say that the “frame” organizes and unifies the art-object and that this is valuable because it “holds together” our experience, which would otherwise be diffuse and shapeless. By contrast, the scene in nature lacks a frame and therefore cannot be grasped and comprehended by the eye and the mind….[A]lthough nature lacks a frame when it simply exists, apart from human perception, this is not true when it is apprehended aesthetically." pg. 47

- "even if we impose a frame on nature and arbitrarily decide to include in our aesthetic apprehension this much and no more of what lies before us, is it ever possible to find a natural scene or object whose formal organization is as aesthetically satisfying as a work of art?" - Professor T. M. Greene. pg. 49.

- Which work of art and which parts of nature are we comparing? And will it not be true that in some cases that some work of art will be better than the actual landscape. Think of any IG photo or video that frames a landscape in away that hides all of its imperfections, captures it at the right time of day, at the right time of weather conditions. But when you go, it's not the same at all. However, there could also be cases where you go and because nature is so transient, you're able to experience a moment that hasn't been captured before, making the moment magical and more valuable than what you would have seen through a photo.

- Art vs nature. no "hard-and-fast dichotomy" pg. 50. In reference to which has more aesthetic value. While art has a frame, it doesn't necessarily mean that the subject is hand-held through an aesthetic experience. If anything, I think a memorable aesthetic experience should be one that takes time and some thinking. Some other examples is the sublime. Can we truly capture this in an artwork? When I tried VR earlier this year, my partner and I created a few rock simluations. There was one where they were giant and floating above us. It made us feel a certain a certain way. The grandeur and the overwhelming sensation of being near these giant floating rocks perhaps felt like the submlime. But ya, not sure if it can be truly captured as if you are on the top of a mountain, or in the middle of the ocean since i think the submlime, or being in nature, requires all of your senses, not just the visual. Or maybe not the visual, but to sense danger.

- Does knowing that art required humans to make it and that there was skilled involed make the appreciation of art more valuable than nature? J.S. - kinship with the person who made it and admire the artist skill.

- If we are to take the aesthetic attitude, should we not care about who made the art though? J.S. if we are preoccupied with their technique, or their personality, or even what their name means (such as a household name or someone who is given attention through media) then we are viewing the art intrumentally.

- Caring about who the artist is. This is a "biographical document". p. 51.

- J.S. says that "nature is deficient in psychological and symbolic interest, compared to art". But when art is mimesis, then wouldn't art have more of an aesthetic value since it's informing the art? Or when we personify nature, are we not seeing ourselves in nature? J.S. states that art-objects embody cultural traditions of a society. But couldn't this be said of nature too, when people identify landmarks as being part of their history? p. 50.

Aesthetic "Relevance"

- p. 52. Best case scenario is when we are engulfed by the experience and there's no separation between subject and object. The subject/object seem to unify? (Hepburn talks about unity in his 1966 in relation to nature.)

- This unity can be broken when the object reminds us about a memory or conjures images. This is because memories or external images are not inherent in the object.

- Bullough, two associations. Emotional-tone and feeling-tone. Emotional is a colour triggers an associative memory, which detracts us from paying attention to the colour. Where feeling-tone is "fushed" with the color (or art). Are both not valid though? To be reminded of a memory, what if that is the intention of the artist? Even if it is a colour choice. As designers, we select colours so that we associate it culture, emotion etc. But for art, if one can have a pesonal experience and be moved by the piece individually, is this not a success since they have connected on a personal level, rather a general? Or perhaps the success of an art piece is to do both.

- J.S. agrees with B. that the first, emotional-tone detracts from the aesthetic attitude because we are not paying attention to the object itself. Instead, we have divereted our attention to our memories. The object is used as an instrument to remind us of something (but again, what if this is the intention?). Also, the example Bullough is using is of a single colour. What about representational art? For "fusing" this is the unity with the object and is considered aesthetic.

- Me: Design is instrumental, so this means it's not art. Although, we use aesthetics in design, it does not mean that it is art.

- Relevance of knowledge about the aesthetic object. Is this relevant to our aesthetic experience? Me: Off the bat, yes because why else are there titles, descriptions, artist statements, art theory, art history. There's a cognitive aspect to art.

- "'Knowledge about' is relevant under three conditions: when it does not weaken or destroy aesthetic attention to the object, when it pertains to the meaning and expressiveness of the object, and when it enhances the quality and signficance of one's immediate aesthetic response to the object". pg. 58.

- Ex. Painting of Christ on the cross. Viewer who is not familiar is told that it's the Son of God to redeem mankind. This piece of information doesn't contribute to the painting itself. Instead, to guide a viewer to examine the figures and how they are positioned, what their facial expressions look like, colours, etc, are part of the aesthetic experience. Although, I'm wondering is this knowledge? To direct our attention to what is already infront of us? I also wonder how do stories play into the aesthetic experience?

- When we are focused on the content and the knowledge or story then we are "simply putting a label on the painting—"Crucifixion"—like calling it a "landscape" or "still life," rather than perceiving it as a wholly individual object." pg. 59. This I can see. Perhaps the first is more about identification rather than aesthetic appreciation.

- Facts. How much to share as a teacher in order to detract from a student's aesthetic perception? I think context is important. Knowing about the time period, knowing about the technology available at the time, influenes what is being made.

- Dangers of comparison. When comparing artworks, we go into an analytical mode rather an aesthetic one (according to J.S.). But as Dickie points out, we are still having an aesthetic experience even if the motive is different since we are still attending to the paintings.

Aesthetic "Surface" and "Meaning"

- D.W. Prall "sensuous 'surface'" pg. 61. Sounds, colours, textures.

- Are only surface qualities part of the aesthetic perception? J.S. thinks no.

- Ulterior purpose, different from a motive. Even if a music student is studying the technicalities of a piece, such as chords, they still listen to the music aesthetically, and then analytically to understand the composition.

- "looking at something 'just for itself'" is what the "surface theory" is saying. Prall suggests that poetry cannot be an art-form because words have meaning. But can't everything have meaning if we want it to have meaning?

- "WE can attend to the words and their meanings disinterestedly." pg. 63. This would be the case of any art, since we can find meaning in representational art by what's being depicted, or through conceptual art, and the ideas. But then we contemplate on the meaning/idea within the aesthetic experience.

- Prall suggests aesthetic experience is only sensory "intuition" is aesthetic but this is limiting.

At the end of the chapters there are questions which I find unusual and fun for a philosophy book.

Q2. "One can become absorbed in a crossword puzzle, a mechanical problem, or the description of some historical epsiode. Is his experience then aesthetic? If not, what differentiates it from aesthetic experience?" To be absorbed by a crossword puzzle is driven by the desire to complete the crossword and to satisfy the intellect and perhaps the ego of being able to overcome a challenging problem. Crosswords have a similar format between them, and I wondering if a new way of presenting crosswords could potentially contribute to the aesthetic experience. This is also the form and function aspect. Form, choice of colour (which is usually driven by economics and not aesthetic), and type choices are decided from the newspaper or the maker of the crossword. If one is to focus on these qualities, then perhaps it could be an aesthetic experience, but usually one is focused on solving the puzzle. The motive of attending to a crossword is also to problem solve.

Notes on The Canon on Polykleitos by Richard Tobin

- "Pythagorean mathematics...considered numbers as geometric entities, having spatial identity." p. 307. This is an interesting idea, that numbers could have an identity and that they mean something within a space.

- "It is proposed that Polykleitos chose a specific member of the human body, the distal phalange of the little finger, as a basic module for his system, and after establishing a length and width for it based on his observation of nature, he used it as a point of departure for determining all the proportions of the human figure. By applying the most basic concepts of Greek geometry-ratio, proportion, symmetria-he developed a system which used a geometric mean in continuous progression." p. 307. Using a body part to determine the proportions and ratios of the human figure. No math involved. -" It should be noted here that Polykleitos went beyond his Canon in the interest of effecting a more "ideal" form." pg. 314.

Bibliography

Aesthetic Attitude | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, [online]. Retrieved from : https://iep.utm.edu/aesthetic-attitude/ [accessed 27 October 2025].

CARROLL, Noël, 1999. Philosophy of art: a contemporary introduction. London : Routledge. Routledge contemporary introductions to philosophy. ISBN 978-0-415-15963-0.

DICKIE, George, 1964. The Myth of the Aesthetic Attitude. American Philosophical Quarterly. Vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 56–65.

Google Trends, Google Trends [online]. Retrieved from : https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&q=aesthetic&hl=en [accessed 30 September 2025].

Google Trends, Google Trends [online]. Retrieved from : https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&q=aesthetics&hl=en [accessed 30 September 2025].

PINKAS, Daniel, 2024. Santayana at the Harvard Camera Club. Limbo: boletín internacional de estudios sobre Santayana. No. 44, pp. 5–41.

NASSAUWEEKLY, 2019. The Problem with Calling Something “Aesthetic.” Nassau Weekly [online]. 3 March 2019. Retrieved from : https://nassauweekly.com/the-problem-with-calling-something-aesthetic/ [accessed 30 September 2025].

SHELLEY, James, 2022. The Concept of the Aesthetic. In : ZALTA, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy [online]. Spring 2022. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved from : https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2022/entries/aesthetic-concept/ [accessed 30 September 2025].

STOLNITZ, Jerome, 1960. The Aesthetic Attitude. In: Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art Criticism: A Critical Introduction [online]. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, pp. 29–64. Available from: https://books.google.ch/books?id=1pIfAAAAIAAJ

SUMMA, Laura Di, 2022. Collecting What? Collecting as an Everyday Aesthetic Act. In : CHEYNE, Peter (ed.), Imperfectionist Aesthetics in Art and Everyday Life. Routledge.

TOBIN, Richard, 1975. The Canon of Polykleitos. American Journal of Archaeology. Vol. 79, no. 4, pp. 307–321. DOI 10.2307/503064.

TO READ LIST

- "Autonomy and Aesthetic Engagement" by Thi Nguyen

- Walter Benjamin’s Kleine Geschichte der Photographie but in Eng

- Sat. author of "Senses of Beauty"

- "Everyday Aesthetics" by Yuriko Saito

- "Ornament and Crime" by Adolf Loo

- "The World as Will and Representation" by Arthur Schopenhauer (1844)

- Immanuel Kant's critiques, third one is Critique of the Power of Judgement (1790)